Render LaTeX in Google Docs

This is for all the students out there!

It turns out that a Google image search for the word “latex” returns many not-safe-for-work images. That’s not the sort of “latex” I’m talking about!

What I’m talking about here is the famous typesetting system, \(\LaTeX\). If you study anything technical at university (or college for readers in the US who seem to make up the majority of my readers!), you would have come across it.

I use Google Docs a lot. I use it at university, at work, and in my personal life. Being a nerd, I frequently need to write equations in Google Docs. Is there a way to write \(\LaTeX\) equations in Google Docs?

Yes, there most certainly is!

How to write and render LaTeX in Google Docs

Install “Auto-LaTeX Equations”

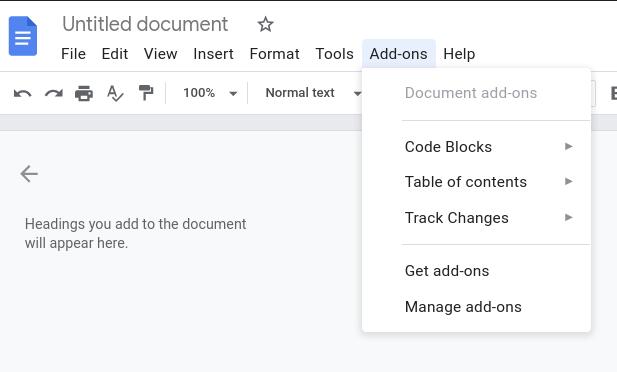

- Open up Google Docs and create a new document.

- Go to “Add-ons” -> “Get add-ons”

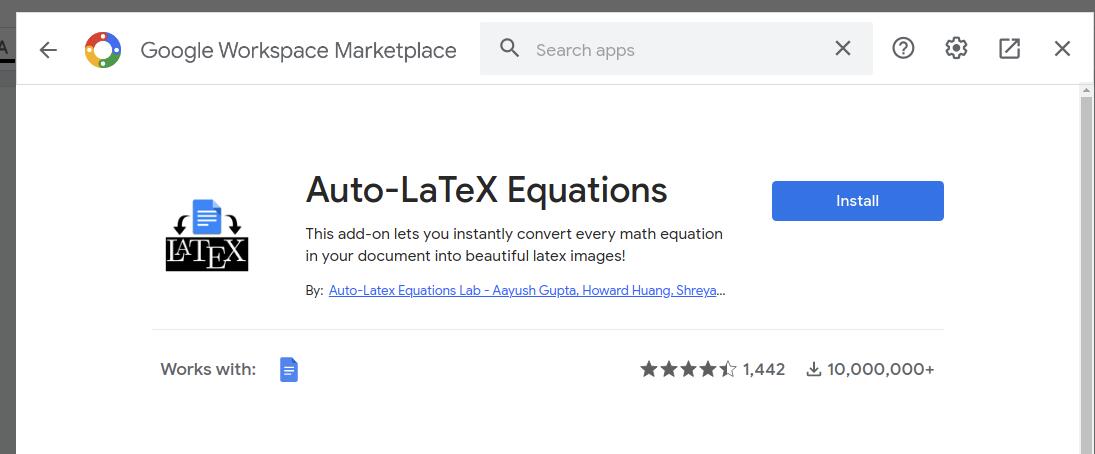

- Search for the word “latex”. The first result should be “Auto-LaTeX Equations. Install it!

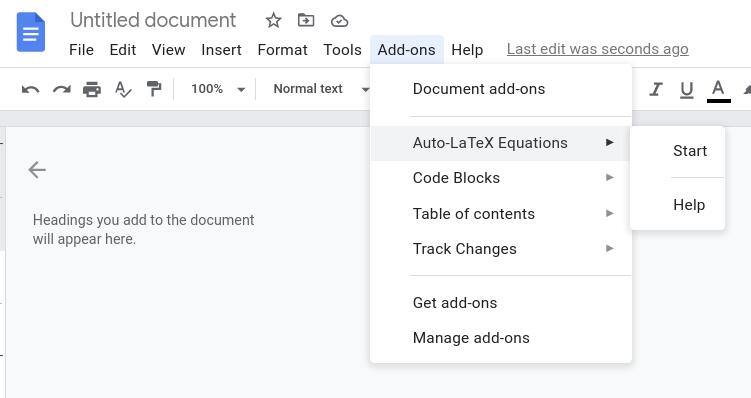

- Once installed, go back to “Add-ons” -> “Auto-LaTeX Equations” -> “Start”

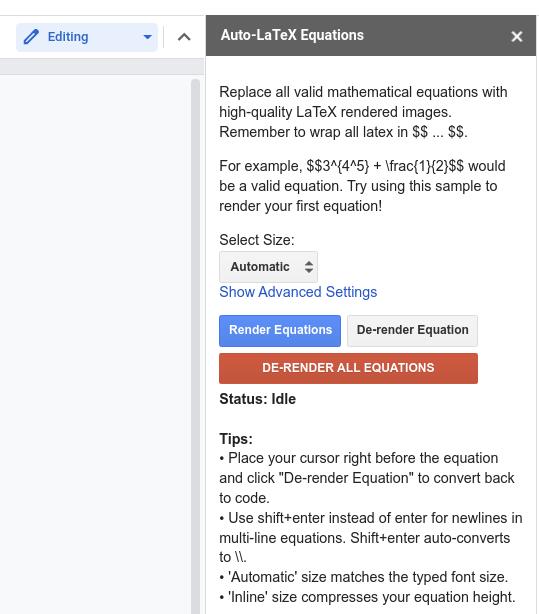

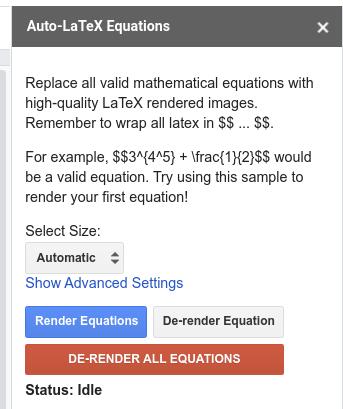

The Auto-LaTeX Equations toolbar should appear on the right-hand side of the screen.

Noice.

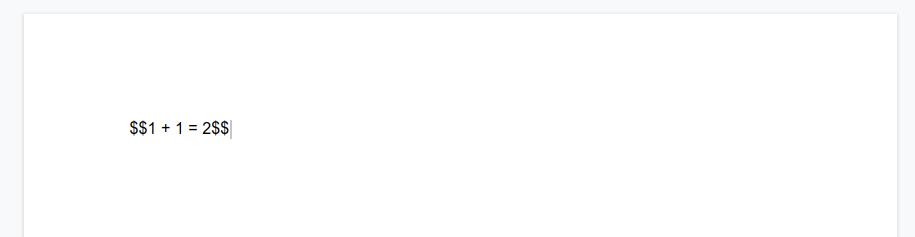

Writing single-line equations

Just wrap what you want to render into Latex in double dollar signs.

Then click on “Render Equations”.

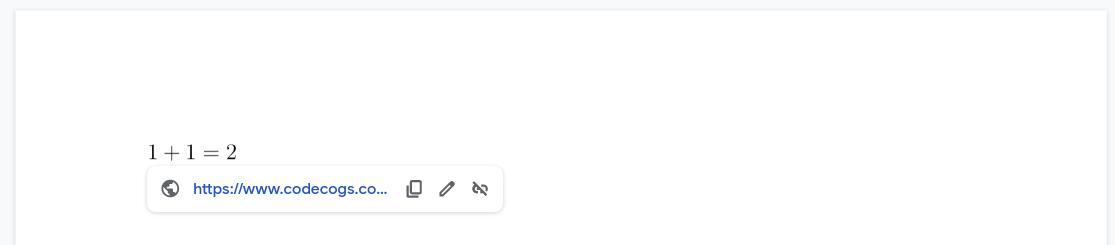

After a little while, you should see something like this!

Nooooooice.

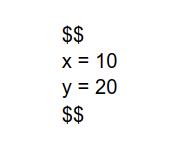

Writing multi-line equations

- Start with two dollar signs, just like with single-line equations. Press

shift + enter. - Type the LaTeX for your first equation. Press

shift + enter. - Type the LaTeX for your second equation. Press

shift + enter. - Type the LaTex for your \(n\)th equation. Press

shift + enter. - Type two dollar signs.

- Press “Render Equations”

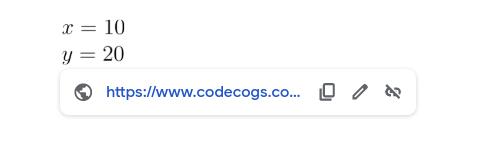

Something like this:

will turn into this:

Noooooooooooooooice.

How to write some mathematical things using LaTeX

Here’s a brain dump of things I commonly use.

Fractions

\frac{1}{2} gives you \(\frac{1}{2}\)

Less than, greater than, less than or equal to, greater than or equal to

< gives you \(<\)

> gives you \(>\)

\leq gives you \(\leq\)

\geq gives you \(\geq\)

Exponents and subscripts

x^i gives you \(x^i\)

x^{2n + 1} gives you \(x^{2n + 1}\)

x_{i} gives you \(x_{i}\)

x_{2n + 1} gives you \(x_{2n + 1}\)

Approximately

\approx gives you \(\approx\)

Equivalence

\equiv gives you \(\equiv\)

Sums and products

\sum\limits_{i=1}^{n} x_i gives you \(\sum\limits_{i=1}^{n} x_i\)

\prod\limits_{i=1}^{n} x_i gives you \(\prod\limits_{i=1}^{n} x_i\)

Partial derivatives

\frac{\partial}{\partial x} x^2 + 3y gives you \(\frac{\partial}{\partial x} x^2 + 3y\)

Gradient

\nabla f gives you \(\nabla f\)

That dot from one of the ways to depict a dot product

x \cdot y gives you \( x \cdot y \)

Big parentheses and brackets

7\left(\frac{x + y}{2}\right) gives you \(7\left(\frac{x + y}{2}\right)\)

z\left[x^2 + 7y\right] gives you \(z\left[x^2 + 7y\right]\)

Adding text in equations

n\text{th} gives you \(n\text{th}\)

Arrows like “implies”

\to and \rightarrow give you \(\to\)

\leftarrow give you \(\leftarrow\)

\implies gives you \(\implies\)

Greek alphabet

They follow a pattern where the lower case variant of the Greek letter begins with a lower case letter. The upper case variant of the same Greek letter begins with an upper case letter. Here are some examples:

\pi and \Pi give you \(\pi\) and \(\Pi\)

\phi and \Phi give you \(\phi\) and \(\Phi\)

\theta and \Theta give you \(\theta\) and \(\Theta\)

Ellipses

\dots gives you \(\dots\)

Proper subsets and subsets

\subset gives you \(\subset\)

\subseteq gives you \(\subseteq\)

Union, intersection

\cup gives you \(\cup\)

\cap gives you \(\cap\)

Aligning equations

Aligning multi-line equations around equal signs can be done by wrapping it in the align environment. Here’s an example:

\begin{align*}

x &= 20y + z \\

z &= \frac{x}{y}

\end{align*}

Conclusion

Nooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooice.

No conclusion, really.

I hope you keep on learning!

Justin